On Cultivating Contentment, Character, and...Bean-Fields

The power of nature, reflection, and self-reliance in Walden by Henry David Thoreau

I’ve finally meandered my way entirely through Walden—admittedly trudging through large portions of it—and have decided that perhaps Thoreau is my least favorite of the transcendentalists.

It’s not that I didn’t find his insights telling; I just didn’t find them nearly as potent or practical as Ralph Waldo Emerson’s, whom I have developed a particular fondness for in my efforts to educate myself before venturing to Concord, Massachusetts.

Much of Walden is spent describing the daily habits and tedious construction—both physically and economically—necessary to support a life of solitude with nuggets of transcendental wisdom scattered about.

Ultimately, I learned more about Thoreau’s beloved bean fields and the economics behind building his cabin than I cared to, but I thoroughly appreciated his (affectionately written) “Reading” chapter and the nature-inspired commentary on matters of contentment and character.

“To read well, that is, to read true books in a true spirit, is a noble exercise, and one that will task the reader more than any exercise which the customs of the day esteem. It requires a training such as the athletes underwent, the steady intention almost of the whole life to this object. Books must be read as deliberately and reservedly as they were written.”

- Henry David Thoreau, Walden

In spite of Thoreau’s criticisms of the surrounding New England society (of which, I sincerely felt he relied on more than he himself realized) there was a cultivation of contentment I both admired and envied. Visitors were not turned away from his humble abode when passing through (and were thoroughly appreciated and entertained), but the solitude Thoreau experienced was seemingly well spent—dare I say even well invested.

The mundane housework, (accompanied by “almost uninterrupted mediation”) is even described as “a pleasant pastime” for Thoreau, which is much more than I can say of my own experiences with mundane housework. 1

“I had this advantage, at least, in my mode of life, over those who were obliged to look abroad for amusement, to society and the theatre, that my life itself was become my amusement and never ceased to be novel. It was a drama of many scenes and without an end. If we were always, indeed, getting our living, and regulating our lives according to the last and best mode we had learned, we should never be troubled with ennui. Follow your genius closely enough, and it will not fail to show you a fresh prospect every hour.”

- Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Of course, in a practical sense, very few (if any) of us can take to the woods alone for any great length of time; but perhaps we can aim to “follow our genius closely enough” amidst the noise of our everyday lives in the hope that it will occasionally show us “a fresh prospect” we did not have before.

There are, I fear, far too many times we seek outward stimulation and revelation, when perhaps we merely need to scrub our kitchen floors in meditation.

(I am writing to myself, here.)

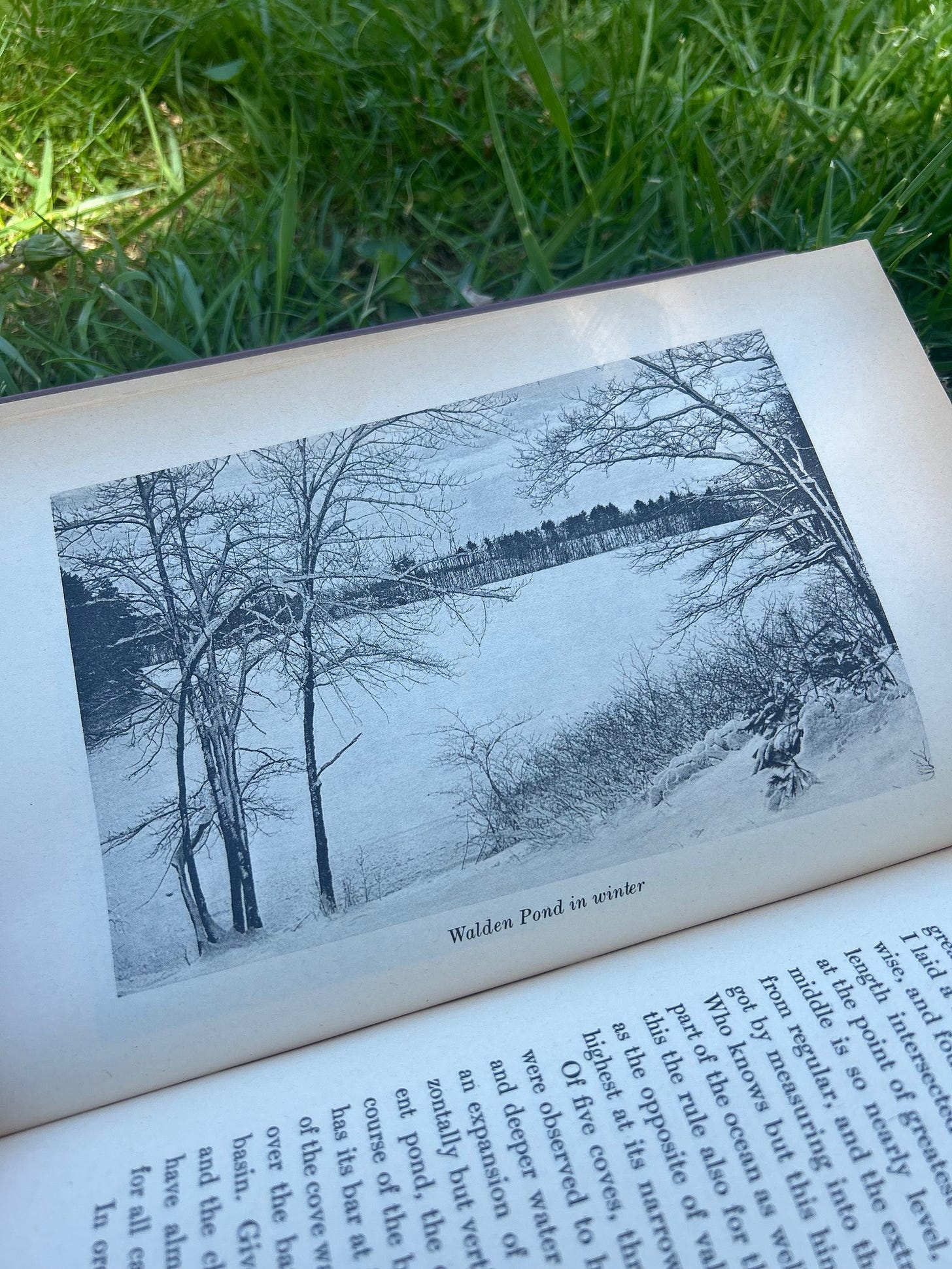

Although I did not encounter as many insights into human nature and the divine as I would have personally preferred in Walden, I did stumble upon a particularly beautiful passage in the chapter titled “The Pond in Winter.”

As my eyes were somewhat glazing over Thoreau’s efforts to measure—and tediously describe said measurements of—White Pond’s depth, I was briefly confronted with a truth I’ve been wrestling with and observing in my own real life experiences for a number of years: the correlation between dramatic (and often tragic) circumstances and the depth of one’s character.

“What I have observed of the pond is no less true in ethics. It is the law of average. Such a rule of the two diameters not only guides us toward the sun in the system and the heart in man, but draw(s) lines through the length and breadth of the aggregate of a man’s particular daily behaviors and waves of life into his coves and inlets, and where they intersect will be the height or depth of his character. Perhaps we need only to know how his shores trend and his adjacent country or circumstances, to infer his depth and concealed bottom. If he is surrounded by mountainous circumstances, an Achilles shore, whose peaks overshadow and are reflected in his bosom, they suggest a corresponding depth in him. But a low and smooth shore proves him shallow on that side. In our bodies, a bold projecting brow falls off to and indicates a corresponding depth of thought.”

- Henry David Thoreau, Walden

I find much of Thoreau’s pond depth analogy to be true, but I am not so sure that the observation stops here: People are far more complicated than ponds and the peaks of life, unfortunately, do not always cultivate a depth of character—but I don’t believe a depth of character can be cultivated without the peaks.

Within the conclusion of Walden, Thoreau joins the chorus of transcendentalists and their call to stay true to oneself, both in thought and in deed, and it is a necessary encouragement—especially in the digital-centered age in which we find ourselves today. It is here where Thoreau once again touches on how crucial it is to find contentment within and away from the external influences we encounter nearly every day.

“However mean your life is, meet it and live it; do not shun it and call it hard names. It is not so bad as you are. It looks poorest when you are richest. The fault-finder will find faults even in paradise. Love your life, poor as it is. You may perhaps have some pleasant, thrilling, glorious hours, even in a poor-house. The setting sun is reflected from the windows of the almshouse as brightly as from the rich man’s abode; the snow melts before its door as early in the spring. I do not see but a quiet mind may live as contentedly there, and have as cheering thoughts, as in a palace.”

-Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Ultimately, I found that it can take Thoreau more time than I’d like to arrive at his most freeing passages; but perhaps that’s exactly why they can feel like rewards at the end of a lengthy mental exercise.

If you have found Thoreau to be one of your favorite transcendentalists and/or early American writers, do not hesitate to comment on what I might be missing or failing to see through his work. (I would appreciate the insight!) I am not entirely sure what I expected to encounter in Walden, but overall I am left feeling as if I have not quite obtained it.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

“Civil Disobedience” by Henry David Thoreau

“Self Reliance” by Ralph Waldo Emerson

“The Poet” by Ralph Waldo Emerson

This Day: Collected & New Sabbath Poems by Wendell Berry

The Stranger in the Woods by Michael Finkel

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard

Thoreau, H. D. (1981). Works of Henry David Thoreau. Crown Publishers, Inc. (pg. 125)

As for survival in a transcendental way using nature, it still rates—because my beans are indeed bountiful! Fun read. Thank you for reminding me of this and taking it on in stride.