Why the Wrestle to Capture the Words Just Might be the Whole Point

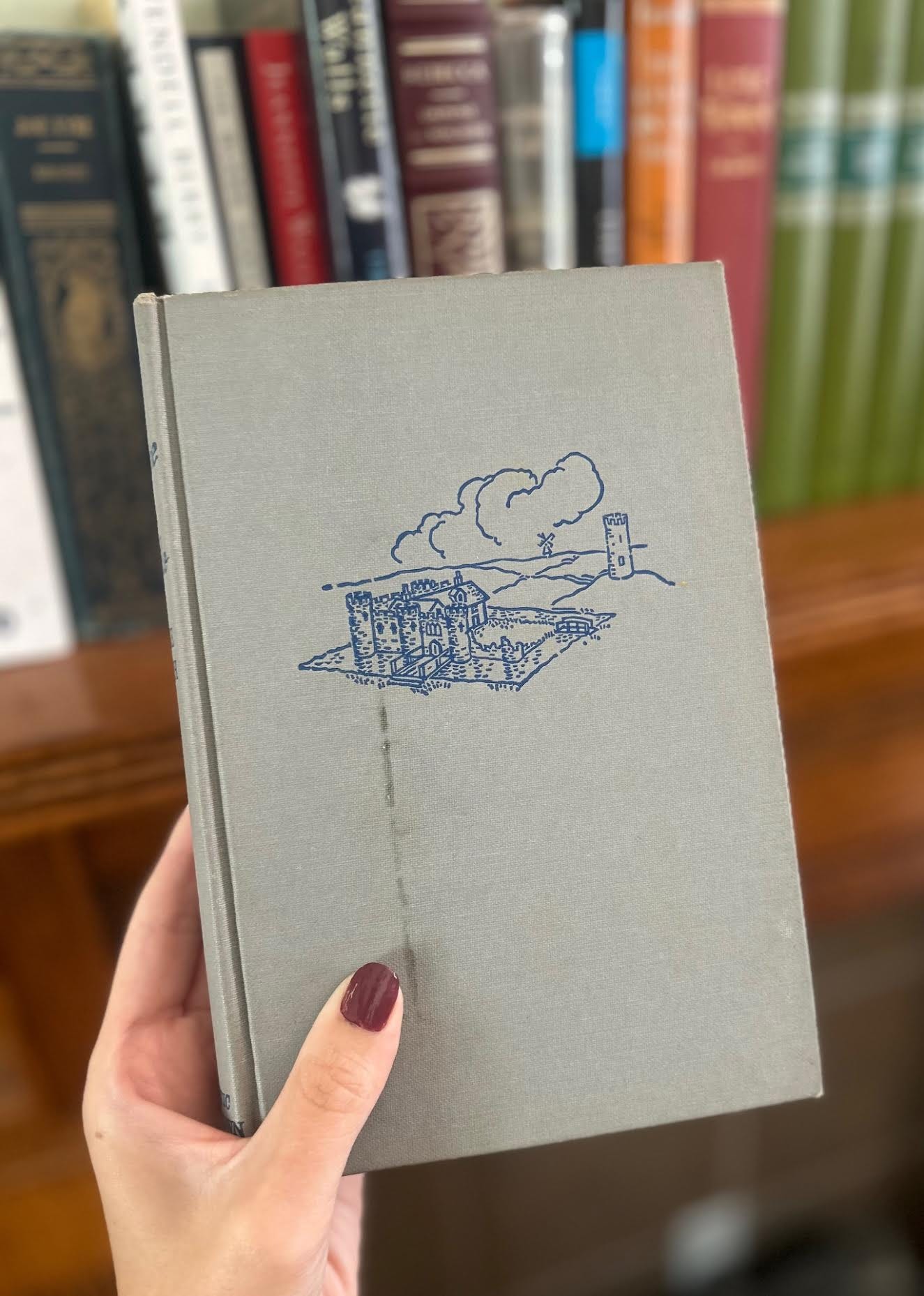

On the indescribable mysteries of love, art, and beauty in I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith

It’s taken me several read-throughs of this most beloved coming-of-age novel to grasp the whole of it, but I think I’ve finally climbed enough rungs of the ladder to reach the top of Belmotte Tower—and the summer mist is rolling over the mound quite beautifully from up here.

Of course, that’s a (fairly dramatic) metaphoric way of describing the understanding I believe I’ve gained from the literary masterpiece that is I Capture the Castle, but it is truly exciting to think I’m finally starting to grasp what Dodie Smith just might have been trying to say through the honest ramblings of Cassandra Mortmain.

(Before reading any further, you really should pair this post with Claude Debussy’s Clair de Lune, as I am fully convinced there is no other way to truly read I Capture the Castle without this particular piece of music lightly playing the background, just as I am fully convinced that all books should—eventually—have soundtracks.)

On the surface, I Capture the Castle is primarily a story about a young girl growing into a woman, discovering just how complicated it can be (and feel) to love someone. Cassandra slowly learns who she is and who she aspires to be, but not without a bit of loss and pain along the way; her life as she knows it is changing, and with it so is she. Her “luxuries” slowly turn from creativity and contemplation to love and anticipation—even if it is the creativity and contemplation that grant her true contentment.

Throughout the novel, we get the feeling that without her journals Cassandra would be quite lost; a sentiment I deeply felt at the very same age. For how else is she to sort out her true feelings about Stephen’s unwavering devotion and Rose’s dishonest engagement to Simon? How else is she to conclude that luxury “takes the edge off joy as well as off sorrow”?1

Writing is free therapy—and Dodie Smith was well ahead of her time in penning the “consciously naive” ramblings of Cassandra Mortmain.2

Even when she is tempted to tear out pages, Cassandra sticks to her sincerity—no matter how potentially embarrassing the words may be should they ever be read by any pair of eyes but her own—and we love her all the more for doing so. She boldly (and accurately) declares that “a journal should not cheat”,3 so we’re left to sort out her worries about her father’s inability to write, her hazy uneasiness about the Fox-Cottons, and her (rather short-lived) resentment of Rose right along with her.

Perhaps if I make myself write I shall find out what is wrong with me.”

-Dodie Smith (Cassandra Mortmain), I Capture the Castle

Most of my readings of I Capture the Castle have let me with a resolved sort of heartbreak that life does not often play out in the ways we wish; this time around I noticed something deeper at play through Cassandra’s lovelorn resolutions.

Although they do not end up together in the way readers might pine for, Cassandra and Simon remain connected in their captivations. Beauty—whether in landscape or music or poetry—speaks to them in ways other characters such as Rose or Neil might not recognize. There is something there we are unmistakably called to pay attention to—and not for the sake of the plot.

“ ‘What is it about the English countryside—why is the beauty so much more than visual? Why does it touch one so?”

-Dodie Smith (Simon Cotton), I Capture the Castle

Interestingly enough, there’s a direct correlation between the mystery of beauty that both Cassandra and Simon are quietly grappling with and Cassandra’s father’s vague (but highly intriguing) literary musings. Although we are not given specific quotations or direct content from Jacob Wrestling, we can slowly infer that it is perhaps a philosophical sort of book about wrestling with one’s convictions—whether they be about love or faith or anything really.

Cassandra grows increasingly frustrated that she cannot wrap her mind around what exactly her father is trying to say through his writing, while at the very same time she is wrestling through her own convictions in her attempts to “capture the castle.”

Jacob wrestling is the point.

Just as her father is not able to plainly—and without the aid of puzzles or visuals—explain what he is getting at, so is beauty itself not so easily explained—and perhaps even love.

Simon does his best to explain the conundrum in the final pages of the novel:

“Because there’s so much that just can’t be said plainly. Try describing what beauty is—plainly—and you’ll see what I mean.”

Then he said that art could state very little—that its whole business was to evoke responses. And that without innovations and experiences—such as father’s—all art would stagnate. “That’s why one ought not to let oneself resent them—though I believe it’s a normal instinct, probably due to subconscious fear of what we don’t understand.”

…

“Look—can you always express just what you want to express in your journal? Does everything go into nice tiny words? Aren’t you constantly driven to metaphor? The first man to use a metaphor was a whale of an innovator—and now we use them almost without realizing it. In a sense your father’s whole work is only an extension of a metaphor.”

When he said that, I had a sudden memory of how difficult it was to describe the feelings I had on Midsummer Eve, and of how I wrote of the day as a cathedral-like avenue. The images that came into my mind then have been linked with that day and with Simon ever since. Yet I could never explain how the image and the reality merge, and how they somehow extend and beautify each other. Was father trying to express things as inexpressible as that…?4

It is not the thing itself—be it beauty or art or love—that we might be trying to define, or obtain, or capture; it is what it evokes in us.

The entire story of I Capture the Castle is Cassandra’s attempt to “capture” something, but in the process it is her attempt itself—her response to the beauty she is attempting to capture—that is really worth anything. The beauty of the castle evokes beauty from Cassandra; an exquisite book is weaved from her journalistic wrestling and Cassandra herself is transformed.

And so, I leave this well-loved story encouraged where I once left it a bit deflated.

It is often not the point to define and conclude and tidy up my musings; it is the wrestling itself, the very attempt to capture something with words, that makes the writing worthwhile.

Smith, Dodie. I Capture the Castle. Little, Brown and Company, 1948, pg. 266

Simon first refers to Cassandra as “consciously naive” on page 64 of the book, but Cassandra herself reiterates these very words several times throughout her reflections. To this description I’ve always wondered: Isn’t it far better to be consciously naive, rather than unconsciously naive?

Smith, Dodie. I Capture the Castle. Little, Brown and Company, 1948, pg. 107

Smith, Dodie. I Capture the Castle. Little, Brown and Company, 1948, pg. 338-339

Such a good book!!