What the Lost Tales of Louisa May Alcott Tell Me

Or rather: Why Writing Outside One's Preference Might Very Well Be Unavoidable

I’ve stumbled upon an unlikely source of encouragement—and it’s all thanks to another glimpse behind the curtain of Louisa May Alcott’s life.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the heart, soul, and literary work of Alcott plunged well ahead of her time. Her abolitionist views and perceptions of love, women, family, and marriage were artfully translated into some of the most beautiful (and humorous) storytelling I believe to ever come out of our nation.

But there is more to Alcott’s literary journey that perhaps not many readers and fans of her work know—and it comes in the form of dark, melodramatic stories.

Themes of mind control, opium addiction, jealousy, and power struggles between men and women abound in the most sensational of Alcott’s stories, which were published anonymously during the 1860s before Alcott began writing Little Women. And we only know of their existence because of extensive research into Alcott’s personal correspondence with publishers—a probe I can’t help but wonder if Alcott would appreciate or despise today. 1

I, consequently, only know of their existence because of rumblings in the Alcott sphere—and because my husband is an absolute maverick when it comes to tracking down the perfect gifts for me.

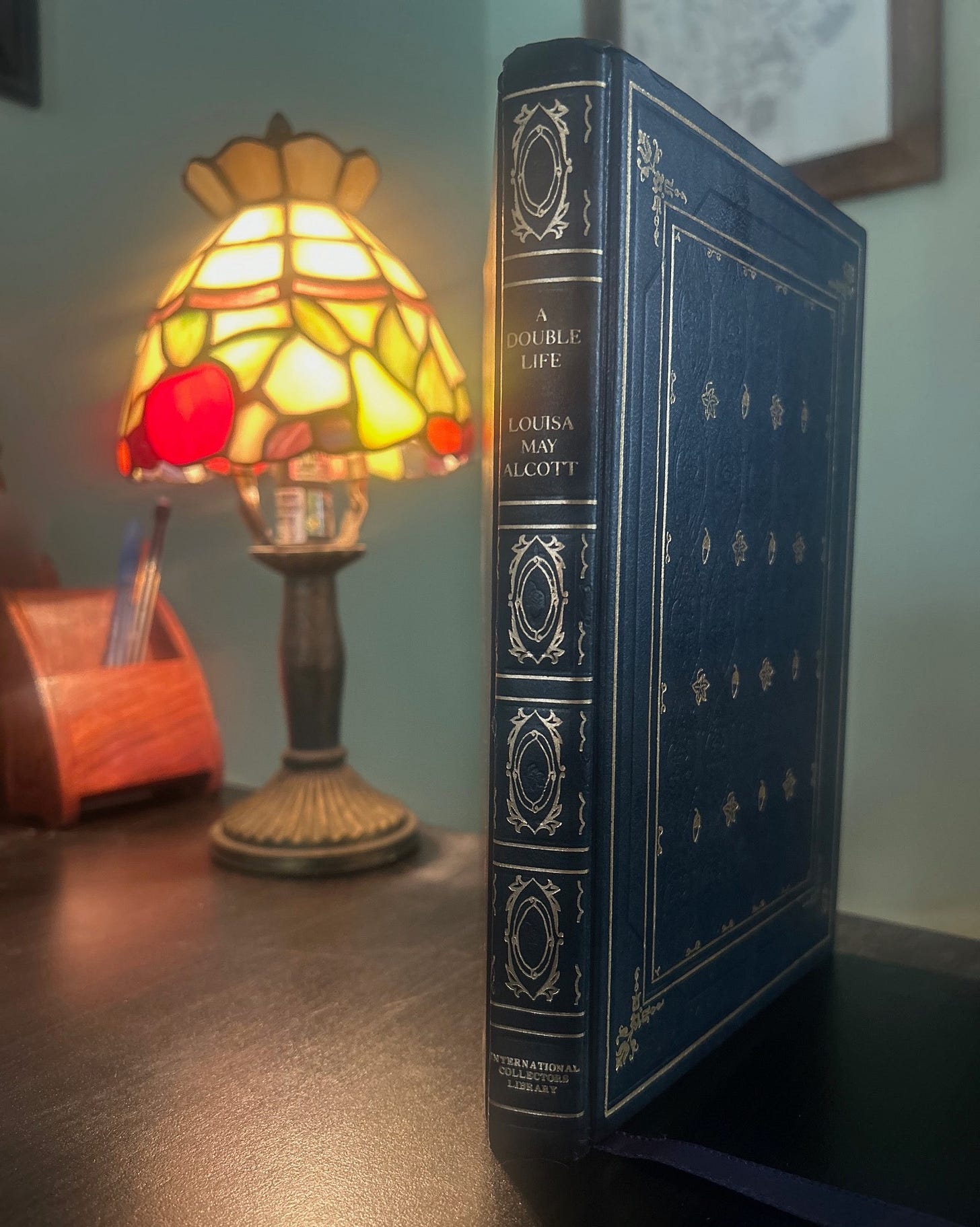

I’ve been leafing through a (very beautiful) 1988 copy of A Double Life: Newly Discovered Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott, produced by the International Collectors Library. The introduction is written by Madeleine B. Stern, and the five stories included are titled as follows:

“A Pair of Eyes; or Modern Magic”

“The Fate of the Forrests”

“A Double Tragedy. An Actor’s Story”

“Ariel. A Legend of the Lighthouse”

“Taming a Tartar”

Strikingly different from the heartfelt tales we know and love of Louisa May Alcott, these were the sort of stories that simply paid better and kept the Alcott family afloat before her famous novel took flight—a certainly familiar theme we observe within the literary wrestlings of Jo March in Little Women, Little Men, and Jo’s Boys.

And it is this very theme of struggle, personal conviction, and eventual triumph that Alcott intermittently explores within her most famous works (and arguably her most famous character) that’s serving as a sort of candle along my own dark, winding path into the writing world.

So far, I find the stories themselves to be fascinating. They are well-written, deliciously paced, and perfectly intriguing; dare I say even reminiscent of the novels and short stories of Daphne du Maurier, a writer I will always have a special affection for. (You can read more about my 17-year-old discovery of her here.)

I have only made my way through two of the stories in A Double Life, but I have to admit that while there are little to no redemptive qualities within the stories to enrich my inner world, I am captivated by the writing and not so easily understood themes and characters. It’s the sort of reading that exposes one to a world that would otherwise remain unknown—even if much of it is melodramatic in nature.

The very existence of these lost tales tell a story I think any (struggling) writer would do well to pay attention to. The most sensational stories of Louisa May Alcott’s career reveal much more than a little-known side to one of America’s most famed authoresses; they reveal a little-known crux behind the writing process I believe many, if not all, writers will confront at an inevitable point in their careers.

Writing talent can surface in more ways than one and wrestling with less than ideal writing is a worthy—and possibly necessary—piece of the writing journey.

Perhaps few (if any) writers write only what they want.

Perhaps most will have to churn out their fair share of poorly paid news features and explore the terrain of ghost writing and wrestle their way through a digital publishing world that’s rapidly (and horridly) infiltrated with AI.

Perhaps some will simply find solace in a Substack—or that old-fashioned pen and composition book.

Ultimately, I don’t know what Alcott would have to say about her anonymous stories being published under her renowned name today. (And I have to wonder what else she published anonymously.) But I like to think that she would appreciate the fact that her lost tales, in spite of their sensational nature, can give modern writers a sort of reality check into the writing and publishing spheres.

I only really know that I most certainly want my personal journals burned upon my demise; those notebooks might keep me sane in the meantime, but what on earth would they do to readers?

(Thankfully, my handwriting is completely illegible—a source of moderate self-loathing that has great potential to serve me well one day, I suppose.)

Anyway, I plan to tell Alcott, in my own special way at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts, that I wholeheartedly love her writing—sensational stories and all.

Alcott, Louisa M. A Double Life: Newly Discovered Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott. Edited by Madeleine B. Stern, Joel Myerson, and Daniel Shealy, International Collectors Library, 1988, pp. 2-3.

I saved these quotes regarding Jo writing things she didn’t love writing after my recent re-read of Little Women because they stood out to me so much. Something about those chapters just rang so true and sounded so deeply personal, almost like the tone shifted a bit. The piece of Alcott’s story you just shared certainly seems to shed some light on why that part of the book had that feeling.

“She took to writing sensation stories, for in those dark ages, even all-perfect America read rubbish.”

“‘People want to be amused, not preached at, you know. Morals don’t sell nowadays.’ Which was not quite a correct statement, by the way.”